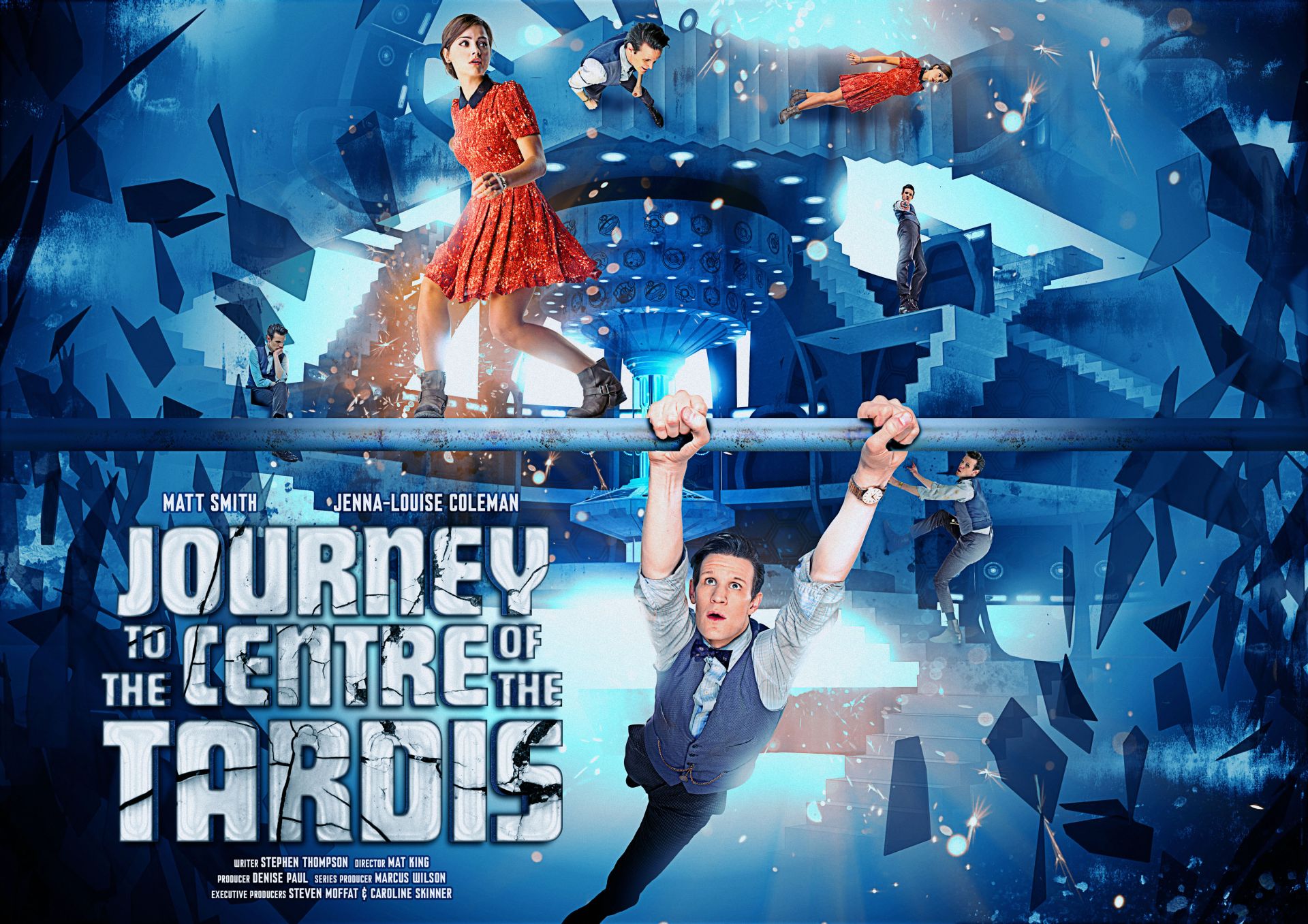

Doctor Who - Journey to the Centre of the TARDIS

Written by Steve Thompson

Directed by Mat King

Broadcast on BBC One - 27 April 2013

This is a bottle episode of sorts, but it’s set inside a very unusual bottle – one that’s really more of a box, infinite indoors, and capable of architectural reconfiguration as well as generating multiple “echoes” of any particular room. Whether this sort of impossible space could ever actually possess a “centre” may be a tough philosophical nut to crack, but it’s a classic episode title nonetheless. And just in case we’re not aware of the rich promise conveyed by ‘Journey to the Centre of the TARDIS’, the Doctor informs the Van Baalen gang that he’s confident he can deliver on “the salvage of a lifetime” (echoing the tagline which accompanied Doctor Who’s 2005 return, although back then it was a trip being promised rather than spectacular flotsam and jetsam).

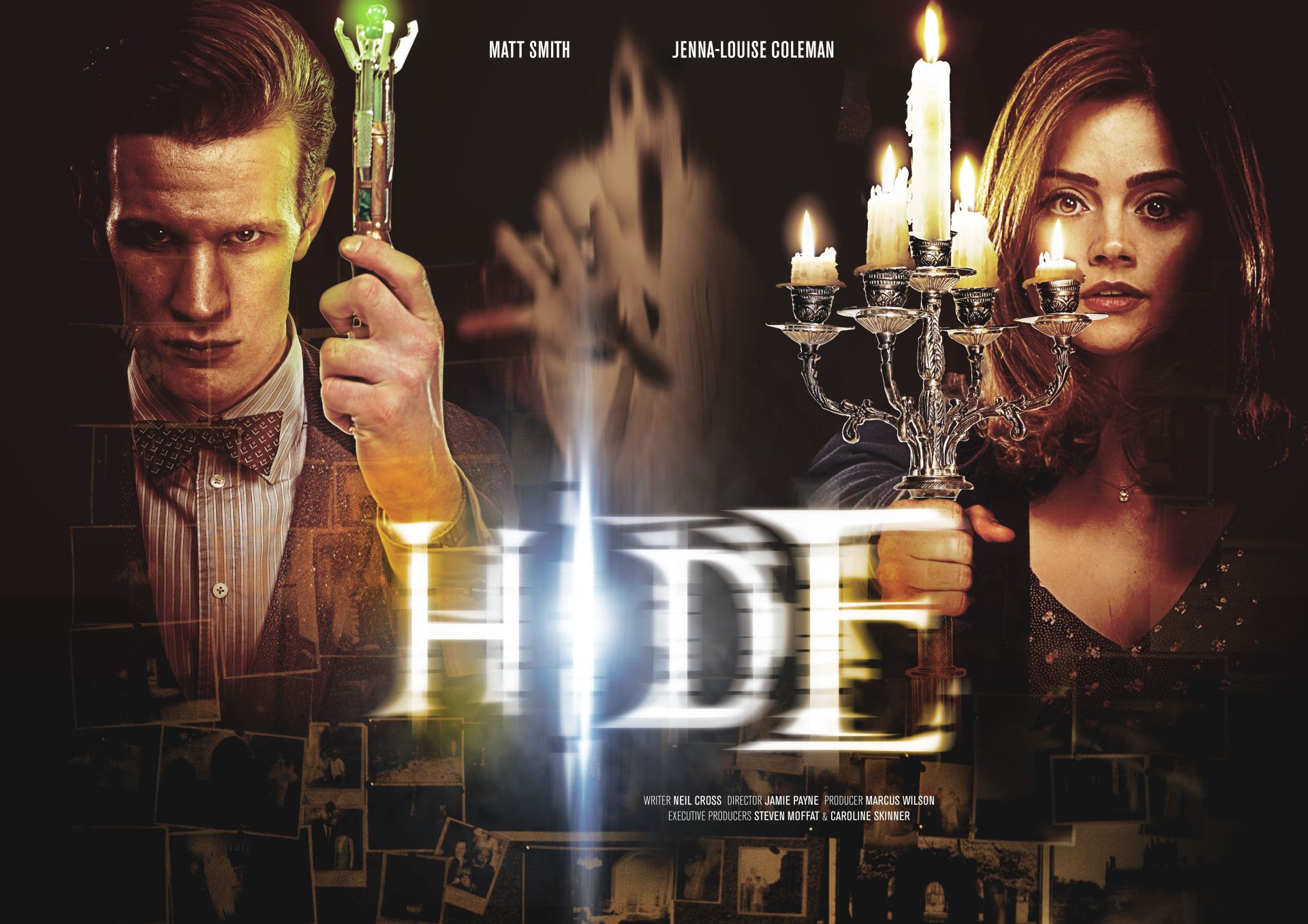

Making the TARDIS the story’s main environment also makes it highly likely, or at least thematically relevant, that time-travel shenanigans will be involved. And sure enough we get a time rift, Time Zombies, frozen time, and a 'History of the Time War'. All set against a ticking clock. Rarely has Doctor Who been this fixated on temporality. I kept waiting for a sequence where assorted clock faces would mysteriously melt, in homage to the very first ‘trapped in the TARDIS’ story from 1964, but plenty of other fan service aimed to press fans’ buttons – including ninth Doctor dialogue from ‘Rose’ and other audio treats, along with glimpses of TARDIS rooms such as the swimming pool and, rather oddly, what appeared to be the telescope from ‘Tooth and Claw’. Does the TARDIS incorporate copies of the Doctor’s previous destinations so he can re-enact adventures at his leisure, in his very own private version of the Doctor Who Experience? It’s one way to break up all the repetitive corridors, I guess.

Although TARDIS-centric storytelling licenses all the chronic time malarkey, this episode’s resolution still comes across as immensely convenient. Yes, it draws attention to the fact that everything can be made better via a “big friendly [reset] button”. And yes, Edward Russell will probably be pleased that this is the first ever Doctor Who story where branding officially saves the day (oops, no, sorry; it’s the wrong sort of brand awareness). More than that, though, you can almost picture Steven Moffat and Steve Thompson chortling over the fact that they’ve come up with the ultimate “handy” solution to a Who story. I say Moffat and Thompson because for me this episode has the exact same problem as ‘The Curse of the Black Spot’. Where that felt too strongly like Thompson imitating Moffat’s preferred tropes (technology gone awry), this was the same hired hand again borrowing showrunner tricks – a rift or crack in time, paradoxes, memory loss, a ‘reveal’ of unexpected identity, and yet another 'reveal' hidden in plain sight (thanks to the torn photograph which we assume is merely set dressing and character background when we first see Gregor). Instead of "Doctor Who in an exciting adventure with the TARDIS", a little too much of this resembled Moffat-era storylining on auto-pilot. It reminded me of series five and its epic rewind through previous stories, but crammed into the space and time of a single tale. I can understand contributing writers wanting to please the big boss, but all this faux-Moffat pastiche arguably produces story predictability rather than elegant brand consistency.

On the plus side, director Mat King made some good choices: the opening ‘walk and talk’ between the Doctor and Clara had them circling the TARDIS console at pace, giving some basic dialogue a whirling dynamism, and nicely prefiguring the characters’ later TARDIS disorientation. And in terms of visual style, King used an unusually large amount of out-of-focus or blurred material for HD, effectively heightening the menace of the Time Zombies. The exploded engine room was also a definite high point, resembling something you’d expect to see in promotional footage for 3D television, whilst its stark white backdrop was brilliantly combined with an absence of incidental music, at least up until the turning point of the Doctor taking Clara’s hand. If these directorial decisions all smartly served the story, then by contrast the end of the pre-credits sequence felt poorly edited and lacking in rhythm – it crashed rather haphazardly into the titles rather than building up to a dramatic punctuation, almost as if King didn’t quite have all the coverage he would’ve wanted.

Greater ethnic diversity is surely something modern Who should be striving for, but casting three black actors to play the shifty Van Baalen team – salvage being represented as boring manual labour lacking in creativity and job satisfaction – struck a debatable note. Another odd moment arrived in the form of Clara’s self-referential “good guys do not have zombie creatures. Rule one, basic storytelling!” Seemingly approaching her travels with the Doctor as if she’s wandered into a “story”, I only hope that the eventual explanation of Clara’s multiple deaths doesn’t involve her being unveiled as some kind of fiction or fabrication. Yet her sudden 'meta' invocation of “basic storytelling” was so ham-fisted it’s tempting to wonder whether this'll carry any further significance in the scheme of things.

There’s also some set-up for ‘The Name of the Doctor’ – presumably material requested by Moffat, just as he’s previously instructed the likes of Matthew Graham and Neil Gaiman on arc duties. It’s a pity, though, that Clara’s reading of 'The History of the Time War' is immediately erased from Doctor Who: ongoing storylines would surely have been more interesting given her unfolding awareness of “the Doctor”. Yet neutralising Clara’s character development is what really makes this a bottle episode, essentially disconnected from what surrounds it. In the end, it’s the guest characters who seem to retain after-images and echoes of what they’ve learnt, with Gregor discovering “a scrap of decency”, whereas over-arching mysteries are safely put back in their box... for the time being.