Doctor Who - The Angels Take Manhattan

Written by Steven Moffat

Directed by Nick Hurran

Broadcast on BBC One - 29 September 2012

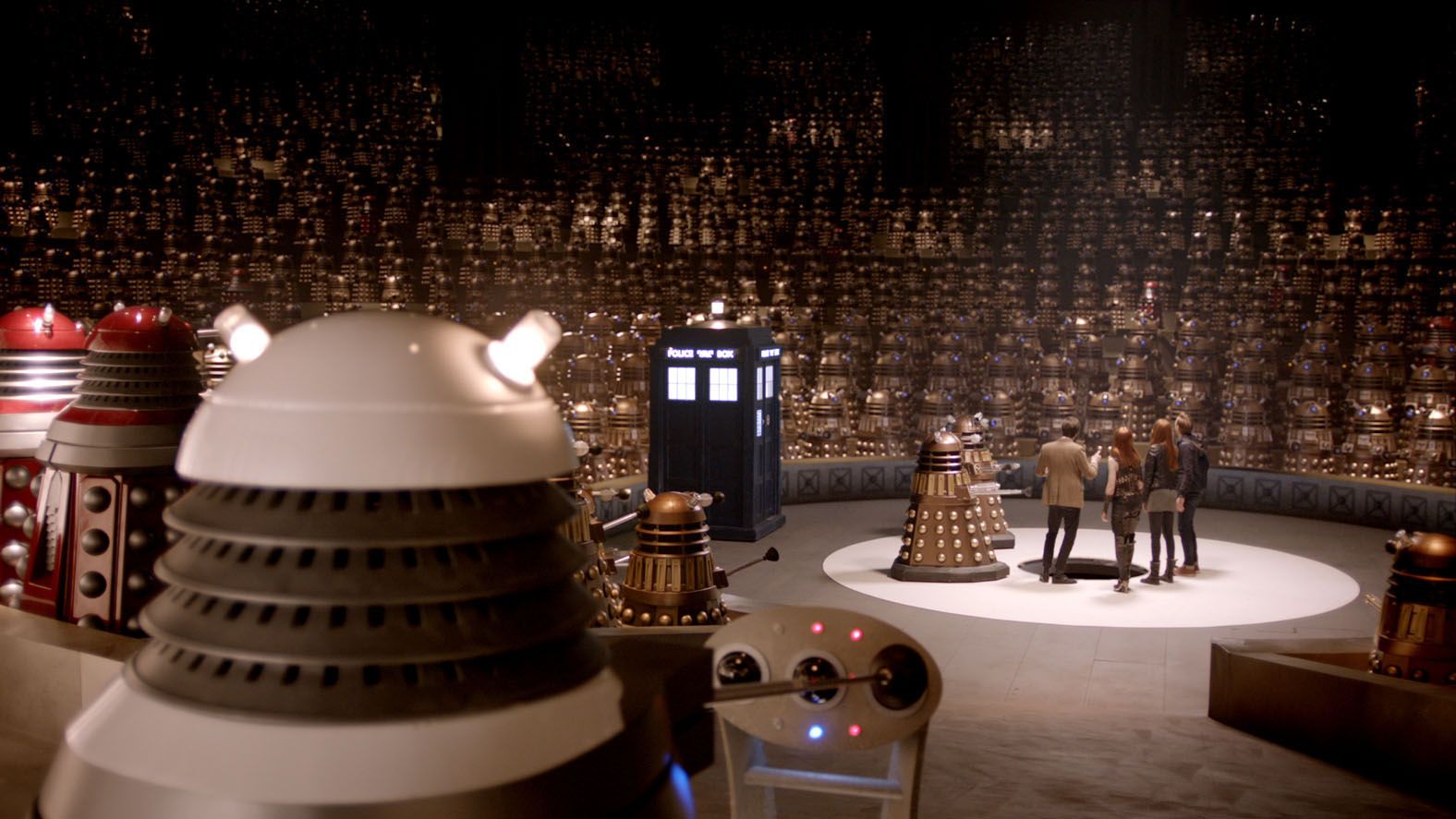

The Angels Take Manhattan delivers in a series of ways: New York’s most infamous statue makes an impressive appearance, and location filming in NYC allows for some iconic Central Park sequences, especially Rory’s visit to Bethesda Fountain. It’s often noir-ish in tone, largely as a result of Melody Malone’s pulp pastiche mixed with repeated shots of dark, shadowy hotel corridors. Nick “slow-mo” Hurran does the business again, and there are some interesting ideas that help develop the Weeping Angels, chiefly their use of a “battery farm.” Surely this could’ve been implemented in any city or major population centre, though; in the end, there’s no strong or necessary link between Manhattan and what the Angels are up to. And do the Angels’ victims spend their entire lives in one hotel room? The plotting here produces some striking, uncanny images of people confronting their older selves, but it doesn’t quite seem fully thought through.

As a series finale, this sometimes suffers from an excess of narrative trickery. It constantly plays with audience expectations surrounding the Ponds’ exit, twisting backwards and forwards between a “final farewell”, death, not-death, death, and, well, a final farewell exactly as promised. For me, the frenetic to-ing and fro-ing got in the way of any sustained emotion; for loss to really hit home, I suspect that its mood has to linger with audiences. But all the whizz-bang scripting rather got in the way of building a powerful, consistent emotion. Rather than heart-felt sentiment and sincerity, this felt too much like a storytelling game, even down to a clever final integration with The Eleventh Hour. Or perhaps it's just that I’ve got a heart of stone.

Steven Moffat also repeats his favourite ontological game; the one where a character suddenly appears in what should be an impossible time and space. We’ve previously had the Doctor abruptly appearing on the TARDIS screen (The Beast Below), and strolling into a recording of the past (A Christmas Carol). This time it’s Rory who moves inside the pages of a novel being read aloud. As a device, it’s perhaps beginning to lose its impact through brazen repetition. Yes, Steven Moffat is an award-winning and massively talented writer, but can’t anyone – exec producer, producer, script editor, whoever – push him not to rely so heavily on tried-and-tested motifs? Just for once, it’d be interesting to see him produce a screenplay devoid of self-referencing Moffatisms.

The Angels Take Manhattan plays yet another game; it needs to find a way to make its ending properly final; a conclusion that can’t be rewritten or reversed. But it does this by reverting to Moffat’s fixation with spoilers: if the Doctor and Amy read ahead, and into their own future, then that future supposedly becomes fixed or “written in stone”. However, this gambit assumes that the events of River’s novel are nothing but the stone-cold truth. What if she’s fabricated, embellished, or dramatised events? I suspect that reading Melody Malone’s adventure shouldn’t quite work in the way that’s suggested. Time can be rewritten, although “not once you’ve read it”… but this can only be true if the act of writing is in no way aesthetically transformative, and amounts to a sort of pure, factual documentation. Storytelling – represented through typewriter clatter and words in extreme close-up – is reduced to a record of events; reading therefore means nothing other than discovering what is, was, and will be. And this attitude towards storytelling extends to the very last story that the Doctor is asked to tell: that of Amy's adventures which have finished, and which are simultaneously yet to come. Oddly, there's absolutely no concept of fiction (or art) within Moffat's artful fiction.

Setting this strangeness aside, “I just have to blink” is a smart inversion of the Angel’s first appearance, and the Angels continue to offer an effective, monstrous presence as Moffat returns them to their Blink modus operandi rather than building on the developments of series five. There’s also a bit of resetting for River, whose role as a criminal, and as the woman who killed the Doctor, seems to have been dissolved along with the Doctor’s legend. The irony is that just at the point that this story insists on fixed points and irrevocable endings, it nevertheless busily rewrites and re-orients Doctor Who’s continuity.

And therein lies the problem, because there can’t be any final ending in a programme like Doctor Who; it’s right and fitting that the Doctor should hate endings, never reading a book’s final page, because Who itself will never have the TV equivalent of a closing sentence. And this is why Moffat has to work so hard to trick viewers into believing in a final ending for the Ponds, even down to a collision of “written in stone” dialogue and written in stone visuals. And down to re-using a shot from The Eleventh Hour, to further cement the notion that Amelia's story is now wholly completed, and rigorously book-ended. But this sense of a closed ending pulls, ultimately, against the televisual and storytelling DNA of Doctor Who, where endings – whatever temporal rules you try and set for them – are always temporary. Afterwords are never the end; they’re just the bit before readers start imagining, and writing their own stories. (Or they’re the bit before the next Christmas Special).

Perhaps the most satisfying thing about The Angels Take Manhattan is that it’s a story about telling and reading stories. The angels get meta. But this remains a satisfaction at writerly cleverness in place of heartbreak and emotional devastation. Don’t get me wrong, I’ll miss Amy and Rory, and this episode does a good job of showing their love for one another. But in the end, there’s not too much to feel actively sad about; they presumably live out their time together, remembering the Doctor and all their escapades, even reaching perfectly respectable ages. Their tragic fate… is to lead ordinary, loving lives. And it’s hard to feel sorry for the Doctor; he has River to look after him, after all, and we already know that he’ll have a new best friend soon enough, as the pleasures of seriality roll ever onward. The Angels Take Manhattan is, at best, a simulation of high emotion – a copy which shouldn’t be mistaken for the real thing. Statuesque and finely crafted, it may be, but it represents an impossible finality in a serialised world.

Written by

Written by

Circle us on Google+

Circle us on Google+